I went to see Mira Schendel’s Monotypes at Hauser & Wirth. The gallery’s on Saville Row and it was early on a Saturday. That was Bill Nighy, my partner said as we crossed the road, but there are so many people who look like Bill Nighy round there that I wasn’t convinced.

The monotypes were laid out flat on waist-high plinths, sandwiched under glass, right by the windows. They were tearing up the road outside and one of the road-workers kept on looking at us looking at the prints. I caught his eye occasionally and wondered if he was going to come in and look at them himself, and whether the gallery attendants would let him in with his work boots on. I felt I was pushing it myself with an old pair of trainers. I really didn’t see Bill Nighy but I think he was probably wearing a navy cashmere overcoat that contrasted in a tasteful way to his “silver” hair.

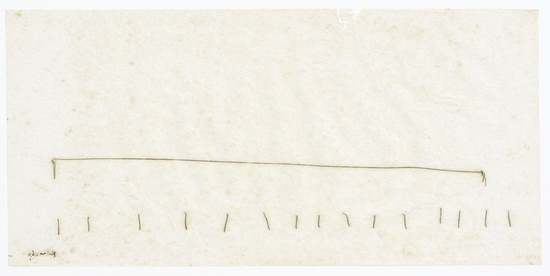

These prints are half a century old. Schendel made them by tracing across small sheets of Japanese paper laid over rollered-out black oil paint. Where she pressed into the paper, it irreversibly picked up the ink. Now the lines she traced have a dark nimbus, a hiss, which I like to imagine developed from the purely material interaction of fibres and oil.

I write “hiss” because when I think of Schendel’s monotypes I think of sound, and the act of transcription between the sounded and the seen. I know a number of them have an elemental religious aspect to them, and also that if you like you could talk about Schendel in relation to Flusser and ontology etcetera, but I’ve always wanted to treat these unlikely, minimal objects as scores.

Schendel was friends with Haroldo de Campos and met Dom Sylvester Houédard when she came to London for her Signals show, so we definitely have a license, if we need one, to think about these intense but fragile and unvociferous prints as part of a noisy world, in fact as part of a ‘verbivocovisual’ system, to borrow a word the concrete poets borrowed from Joyce. If they’re scores, they function to preserve, or distort, or transform material, as a condition of it moving from state to state.

But does a score need to have an object? Does it need to score something? Is it possible to have an intransitive score? Because actually that’s what the prints seem to suggest (the wordless ones in particular). Hans-Jörg Rheinberger mentions a case from virology research, writing that “for forty years the experimental system was in a sense oscillating around an ‘epistemic thing’ that constantly escaped fixation”. In a similar way, the object of knowledge of these prints also appears to escapes fixation; it’s never quite specifiable as such.

There’s a kind of seismic quality to these loose groups of monotypes and I think that connects to the way they oscillate around their object. The way something vibratory is not a thing but a relationship. Outside they started drilling the tarmac again, using a minicat with a pneumatic attachment. We could all feel it through the dark concrete floor.

Image: Mira Schendel, Untitled (from Horizontals/Horizontais), 1964. Exhibition details here. Source for Rheinberger quote here – thanks to Des Fitzgerald and Felicity Callard for pointing me towards it.